Figure 1. All college classes require some form of writing. Investing some time in refining your writing skills so that you are a more confident, skilled, and efficient writer will pay dividends in the long run.

Writing assignments can be as varied as the instructors who assign them. Some assignments are explicit about what exactly you’ll need to do, in what order, and how it will be graded. Others are more open-ended, leaving you to determine the best path toward completing the project. Most fall somewhere in the middle, containing details about some aspects but leaving other assumptions unstated. It’s important to remember that your first resource for getting clarification about an assignment is your instructor—they will be very willing to talk out ideas with you, to be sure you’re prepared at each step to do well with the writing.

Writing in college is usually a response to class materials—an assigned reading, a discussion in class, an experiment in a lab. Generally speaking, these writing tasks can be divided into three broad categories: summary assignments, defined-topic assignments, and undefined-topic assignments.

Empire State College offers an Assignment Calculator to help you plan ahead for your writing assignment. Just plug in the date you plan to get started and the date it is due, and the calculator will help break it down into manageable chunks.

Being asked to summarize a source is a common task in many types of writing. It can also seem like a straightforward task: simply restate, in shorter form, what the source says. A lot of advanced skills are hidden in this seemingly simple assignment, however.

An effective summary does the following:

That last point is often the most challenging: we are opinionated creatures, by nature, and it can be very difficult to keep our opinions from creeping into a summary. A summary is meant to be completely neutral.

In college-level writing, assignments that are only summary are rare. That said, many types of writing tasks contain at least some element of summary, from a biology report that explains what happened during a chemical process, to an analysis essay that requires you to explain what several prominent positions about gun control are, as a component of comparing them against one another.

This automatically lets your readers know your intentions and that you’re covering the work of another author.

Omit nothing important and strive for overall coherence through appropriate transitions. Write using “summarizing language.” Your reader needs to be reminded that this is not your own work. Use phrases like the article claims, the author suggests, etc.

This is not a statement of your own point of view, however; it should reflect the significance of the book or article from the author’s standpoint.

Figure 2. Many writing assignments will have a specific prompt that sends you first to your textbook, and then to outside resources to gather information.

Often, the handout or other written text explaining the assignment—what professors call the assignment prompt —will explain the purpose of the assignment and the required parameters (length, number and type of sources, referencing style, etc.).

Also, don’t forget to check the rubric, if there is one, to understand how your writing will be assessed. After analyzing the prompt and the rubric, you should have a better sense of what kind of writing you are expected to produce.

Sometimes, though—especially when you are new to a field—you will encounter the baffling situation in which you comprehend every single sentence in the prompt but still have absolutely no idea how to approach the assignment! In a situation like that, consider the following tips:

Many writing tasks will ask you to address a particular topic or a narrow set of topic options. Defined-topic writing assignments are used primarily to identify your familiarity with the subject matter. (Discuss the use of dialect in Their Eyes Were Watching God, for example.)

Remember, even when you’re asked to “show how” or “illustrate,” you’re still being asked to make an argument. You must shape and focus your discussion or analysis so that it supports a claim that you discovered and formulated and that all of your discussion and explanation develops and supports.

Another writing assignment you’ll potentially encounter is one in which the topic may be only broadly identified (“water conservation” in an ecology course, for instance, or “the Dust Bowl” in a U.S. History course), or even completely open (“compose an argumentative research essay on a subject of your choice”).

Figure 3. For open-ended assignments, it’s best to pick something that interests you personally.

Where defined-topic essays demonstrate your knowledge of the content, undefined-topic assignments are used to demonstrate your skills—your ability to perform academic research, to synthesize ideas, and to apply the various stages of the writing process.

The first hurdle with this type of task is to find a focus that interests you. Don’t just pick something you feel will be “easy to write about” or that you think you already know a lot about —those almost always turn out to be false assumptions. Instead, you’ll get the most value out of, and find it easier to work on, a topic that intrigues you personally or a topic about which you have a genuine curiosity.

The same getting-started ideas described for defined-topic assignments will help with these kinds of projects, too. You can also try talking with your instructor or a writing tutor (at your college’s writing center) to help brainstorm ideas and make sure you’re on track.

Writing is not a linear process, so writing your essay, researching, rewriting, and adjusting are all part of the process. Below are some tips to keep in mind as you approach and manage your assignment.

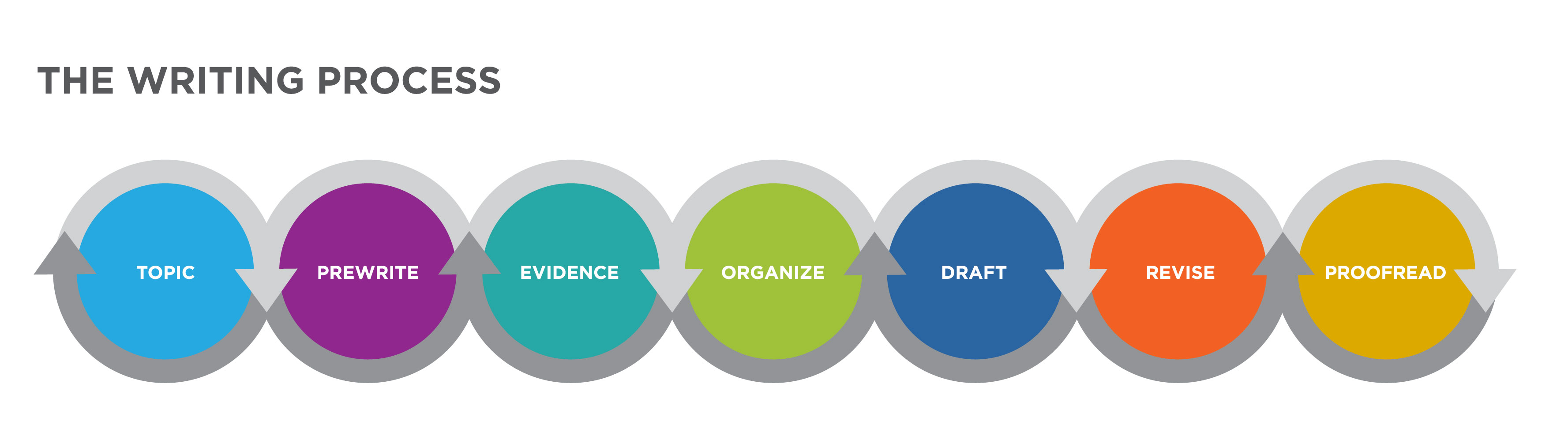

Figure 4. Writing is a recursive process that begins with examining the topic and prewriting.

Write down topic ideas. If you have been assigned a particular topic or focus, it still might be possible to narrow it down or personalize it to your own interests.

If you have been given an open-ended essay assignment, the topic should be something that allows you to enjoy working with the writing process. Select a topic that you’ll want to think about, read about, and write about for several weeks, without getting bored.

Figure 5. Just getting started is sometimes the most difficult part of writing. Freewriting and planning to write multiple drafts can help you dive in.

If you’re writing about a subject you’re not an expert on and want to make sure you are presenting the topic or information realistically, look up the information or seek out an expert to ask questions.

It doesn’t matter how many spelling errors or weak adjectives you have in it. Your draft can be very rough! Jot down those random uncategorized thoughts. Write down anything you think of that you want included in your writing and worry about organizing and polishing everything later.

Set a timer and write continuously until that time is up. Don’t worry about what you write, just keeping moving your pencil on the page or typing something (anything!) into the computer.

Licenses and Attributions CC licensed content, Original